August - What’s Past is Prologue

August 30, 2025

“What’s Past is Prologue”

Observations On the Current Market Environment

What a month!

August is often dubbed one of the most treacherous months for financial markets allegedly due to low trading volume as summer holidays reduce oversight and liquidity while the titans of Wall Street vacation in the Hamptons. But this August saw record volumes across global equity markets and exchanges.

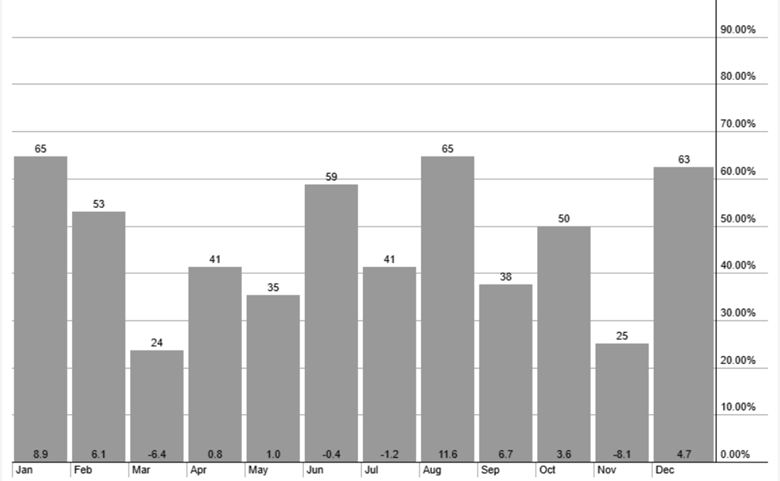

Heightened volatility is also historically an August event. Over the past 20 years, the VIX has finished higher 65% of the time at the end of August. The average increase is 11.6%, which is greater than any other month during the period.

But like many reliable market maxims, this was not the case this year with the VIX starting at a slightly lower than average level and drifting steadily downward for most of the month. Not a typical August by historical standards.

Being a market observer for over forty years, and a student of market history for that same period, it seemed worth going back and trying to remember a similar market ‘feel". A prior period where events and policy echo the current day.

It could be argued that a similar setup also began in August, but the year was 1998. Russia, weighed down by debt and collapsing oil prices, defaulted on its sovereign bonds which after the fall of the Berlin Wall had been gobbled up by hedge funds using the notorious “carry trade”. Quickly global credit markets began to seize up, as rumors of a pending hedge fund collapse circulated across trading desks. The chatter turned out to be true as the near-fatal unraveling of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) a hedge fund celebrated for its Nobel Prize-winning partners and mathematical trading models went down.

Leveraged to the hilt with a Russian sovereign bond carry trade, LTCM’s positions collapsed when short term debt liquidity vanished, threatening to drag several major U.S. banks down with it. A $3.6 billion, Fed-orchestrated bailout in early September prevented a catastrophe.

In Roger Lowenstein’s excellent book, When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management, he tells the story of the bailout through first person interviews of all the major characters involved in the event. According to the book, Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Fed invited the CEO’s of Bankers Trust, Bear Stearns, Chase Manhattan, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Dean Witter, and Salomon Smith Barney, to the Fed's board-room in New York on September 2, 1998. They were also joined by the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange and the representatives of several European banks. The investment banks were “invited” to enter a consortium to fund the bailout of LTCM. The Federal Reserve raised $4 billion from the investment and commercial banks to stabilize LTCM. The group "bickered and backstabbed," according to Lowenstein, but by December 1999, the bailout was complete, and LTCM was again functioning under a new name.

Wall Street quickly recovered from the fears of a potential systemic meltdown. The shock exposed the fragility of highly leveraged strategies. LTCM had built enormous positions using complex derivatives, assuming market conditions would remain stable. Alan Greenspan’s rapid response of cutting interest rates and flooding the system with liquidity calmed the panic and reignited risk appetite. Markets rebounded sharply, and by early 1999, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had erased its crisis-era losses. Wall Street’s takeaway? Volatility was temporary; the Fed was the ultimate safety net. This belief became known as the “Greenspan Put” with the implicit assumption that policymakers would rescue markets from steep declines, and the "plunge protection team" as it became known among traders, would have your back.

The rapid recovery set the stage for the dot-com bubble of 1999–2000. Investors interpreted the Fed’s intervention—not only the LTCM rescue but also a series of rate cuts—as a signal that liquidity would always be available in a crisis. Risk-taking surged, particularly in technology and internet stocks, which were gaining cultural prominence amid optimism about a new digital economy.

At the same time, politically, the U.S. faced turbulence in 1998 with the Monica Lewinsky scandal and the looming impeachment of President Bill Clinton. Yet markets seemed largely indifferent, focusing instead on monetary policy and the burgeoning tech boom. By 1999, this mindset evolved into what Alan Greenspan termed “irrational exuberance,” as speculative capital poured into companies with little revenue but held out the vast promises of internet-driven growth.

Those who lived through the dot com era might feel a déjà vu in today’s current market environment. The parallels seem notable.

Coming off several years of post-pandemic excess liquidity delivered by the Fed and the Inflation Reduction Act, the markets have moved steadily higher, buoyed by the notion that There Is No Alternative (TINA) and a Fear of Missing Out (FOMO).

Quant funds and algorithmic trading strategies drive much of the market activity with short term trading representing a majority of daily trading volume. Activity in 0DTE (Zero Days Till Expiration), options contracts that expire and become void on the same trading day, once an esoteric derivative strategy, has become mainstream and popular among retail traders.

There is also not a time in memory where such a large multiple of potentially market impacting political variables have played out in real time. Yet again as in 1998, the markets seem largely indifferent. The idea of the US bombing Iranian nuclear sites without the global energy and financial markets going into a frenzy of volatility would not have been believable if it recently had not seen it in real time.

And, much like the dot com era and the future internet economy, the promise of an AI revolution has taken hold. Immense amounts of capital are pouring into AI related infrastructure and AI technology with no proven profitable business model or any clear understanding of the potential return on invested capital.

|

Key

Parallel |

1998–2000

Context |

Today’s

Call |

|

Leverage

& Margin |

LTCM’s

massive leverage spurred collapse |

Margin debt

at historic highs, systemic vulnerability |

|

Market

Concentration |

A few

dot-coms dominated indices |

Mag 7 tech

giants (AI-enabled) dominate today |

|

Speculative

Frenzy |

Dot-com

investments often lacked profits |

Many AI firms

enjoy sky-high valuations without earnings |

|

Narrative-Driven

Investing |

“New economy”

hype overshadowed caution |

AI

storytelling, meme stock fervor driving markets |

|

Central

Bank Backstop |

Fed rescued

LTCM, bolstering risk appetite |

Continuing

policy support may encourage overreach |

The ebullience that seems to be gripping today’s investment landscape, marked by soaring tech stocks, frenzied IPOs, and unprecedented retail participation feel like the same factors that culminated in the dot-com bubble’s spectacular peak in early 2000. But the seeds of that euphoria were sown in the late summer of 1998, when a global crisis convinced Wall Street that safety nets were woven deep into the fabric of the financial system and they only path for the market was higher.

A fair observer, reflecting on the lessons of 1998–2000 and today’s parallels, might conclude that while history never repeats itself exactly, it often rhymes in ways that challenge investor discipline. The same mix of abundant liquidity, technological promise, and belief in central bank intervention that fueled the dot-com boom seem present again. But now they are amplified by faster markets, larger players, and AI-driven narratives. It probably will not end up in a spectacular decline as in 2000, but one can reasonably argue that expected market returns will likely be more subdued going forward than they have been over the past few years.

Rick Imperiale

Writing as The Fair Observer